ANN ARBOR – Michigan lawmakers are beginning to publicly grapple with a question that until recently was playing out mostly behind closed doors: Can the state absorb a surge of massive data centers without straining the electric grid, raising rates for residents, or sidelining local communities?

That question took center stage this week as a Michigan House subcommittee heard testimony from energy experts, environmental advocates, and local officials on the rapid growth of large-scale data centers—many tied to artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and hyperscale storage.

The hearing reflects a growing realization in Lansing that data centers are no longer niche industrial projects. They are fast becoming some of the most energy-intensive facilities ever proposed in Michigan, with implications that reach far beyond zoning boards and economic-development press releases.

From Economic Win to Policy Stress Test

For state leaders, the appeal is obvious. Data centers bring billions in capital investment, high-skill jobs, and prestige tied to next-generation technologies like AI.

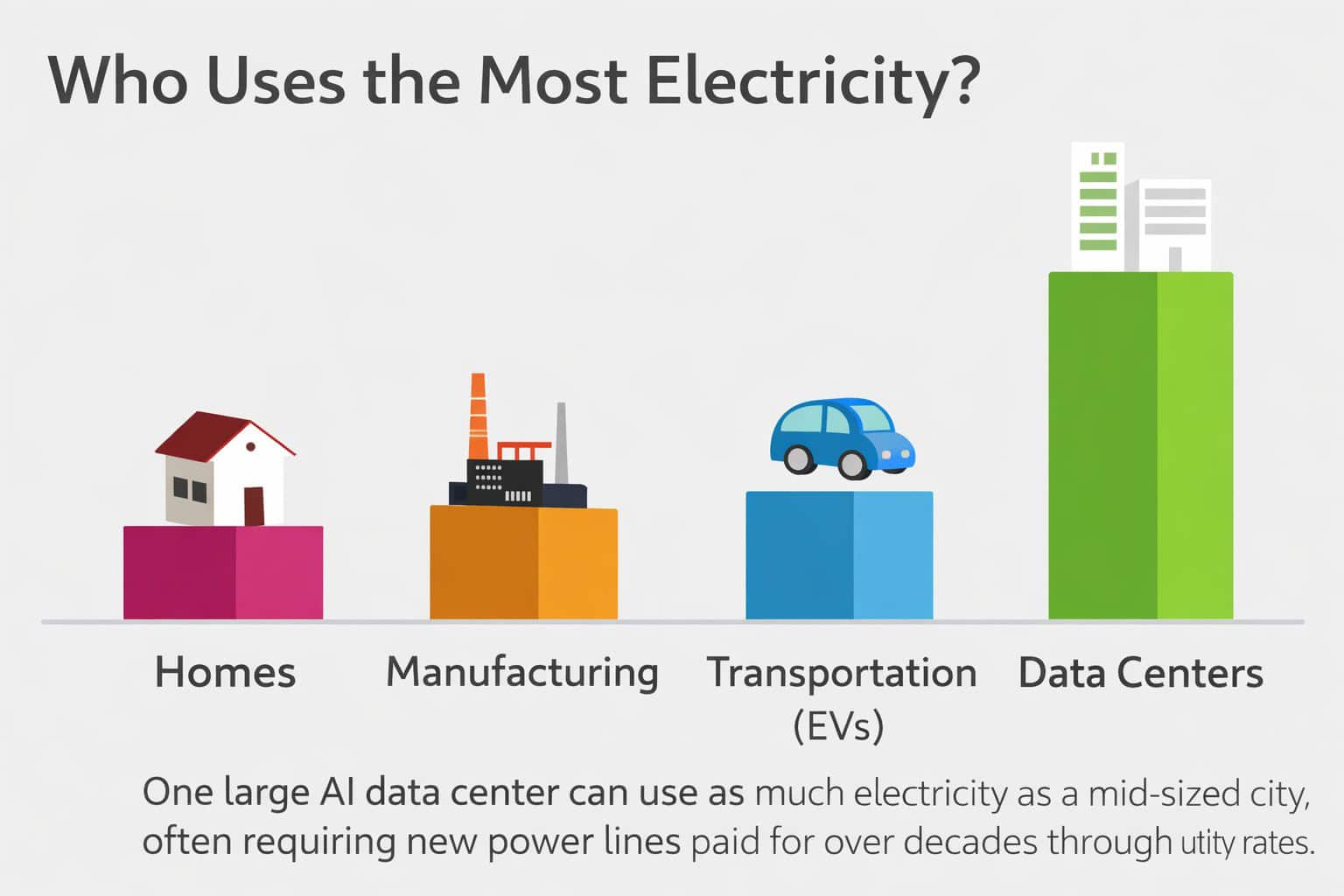

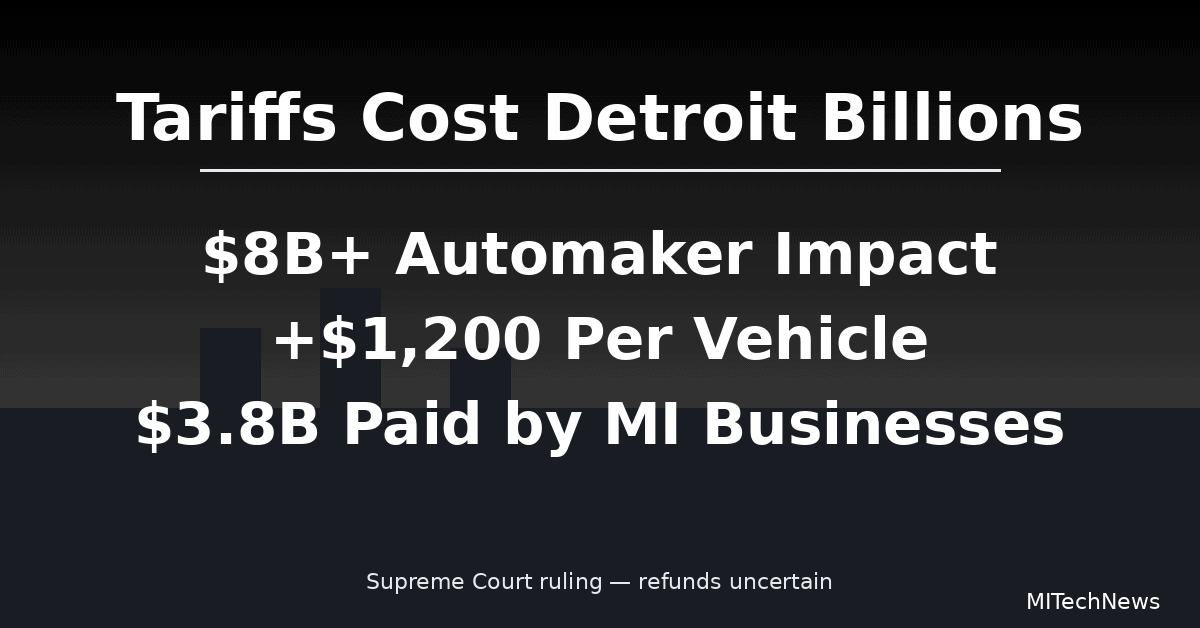

But testimony before lawmakers underscored a more complicated reality: a single large data center can consume as much electricity as a mid-sized city, often requiring new transmission lines, substations, and long-term power contracts.

Those infrastructure costs don’t disappear. Consumer advocates warned that, without clear policy guardrails, residential and small-business ratepayers could end up subsidizing grid upgrades needed to serve a handful of mega-users.

The OpenAI Project Outside Ann Arbor Changed the Conversation

Much of the legislative urgency traces back to the proposed OpenAI-linked data center in Saline Township, just outside Ann Arbor—one of the largest AI-related infrastructure projects ever contemplated in Michigan.

That project, which involves partners including Oracle and real-estate developers specializing in hyperscale facilities, brought national attention—and local backlash—almost overnight. Residents raised concerns about:

-

Electricity demand and long-term rate impacts

-

Water use and heat discharge

-

Tax incentives negotiated with limited public input

-

Whether local governments had meaningful leverage once state-level approvals were in motion

The Saline proposal became a case study in how quickly data-center deals can outpace public understanding, forcing lawmakers to confront gaps in oversight that were never designed for AI-era infrastructure.

Grid Capacity Is the Silent Constraint

Energy experts told the House panel that Michigan’s grid can handle current demand—but future demand is another story.

Michigan is already juggling:

-

Electrification of vehicles and manufacturing

-

Retiring coal plants

-

Increased reliance on renewable generation

-

Aging transmission infrastructure

Layering multiple hyperscale data centers onto that system, witnesses warned, could accelerate the need for new high-voltage transmission lines, a process that is expensive, slow, and often deeply controversial at the local level.

This concern echoes earlier MITechNews reporting on how data-center growth is quietly reshaping grid-planning decisions across the state—sometimes before residents even realize projects are under consideration.

Local Control vs. Statewide Strategy

Another theme to emerge from the hearing: Who really decides where these projects go?

Municipal leaders from communities like Sterling Heights—where officials recently enacted a temporary moratorium on new data-center proposals—argued that local governments are being asked to absorb land-use and infrastructure impacts while major decisions are driven at the state or utility level.

Lawmakers appeared increasingly sympathetic to the idea that Michigan needs:

- Clearer siting standards