ANN ARBOR – Scientists are increasingly alarmed that Thwaites Glacier, the massive Antarctic ice stream nicknamed the Doomsday Glacier, is edging closer to a point of no return. A new study by the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration reveals a dramatic increase in fractures across the glacier’s floating ice shelf over the past two decades—a structural weakening that accelerates ice flow into the ocean and brings the glacier closer to irreversible collapse.

How Thwaites Is Falling Apart

Thwaites’ eastern ice shelf is anchored at its northern end by a ridge on the ocean floor. But satellite observations show that cracks in the shelf have grown from around 165 km in 2002 to roughly 336 km in 2021, and their patterns suggest a feedback loop: more cracks let ice move faster, and faster ice generates more cracks.

Since about 2017, the shelf’s connection to its anchoring ridge has weakened or broken, accelerating Ice flow upstream and weakening structural stability. The study documents this deterioration in stages, including a shift in how stress is distributed through the ice and a significant increase in smaller fractures—signs that the shelf is nearing a point where recovery is unlikely.

Because Thwaites sits on a reverse-sloped bed that dips inland toward the continent, retreat tends to become self-reinforcing: once warm seawater gets under the ice, it promotes more melt, making stabilization harder.

A Canary in the Coal Mine for Global Warming

This evolving collapse isn’t just about one glacier. Climatic and ocean warming are melting Thwaites from below, weakening its structure and triggering stress changes that could foreshadow similar destabilization in other Antarctic ice shelves. That’s why many scientists describe Thwaites as a climate “canary in the coal mine”—a sensitive early-warning indicator of deeper changes in the global climate system.

What happens at Thwaites helps refine models of ice-sheet behavior under warming scenarios and shows how even modest warming can trigger self-reinforcing processes that amplify change.

Sea-Level Rise: Why Inches Matter

On its own, Thwaites holds enough ice to raise global sea levels by roughly two feet. More concerning, it acts as a keystone holding back neighboring glaciers. If Thwaites gives way, large portions of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could destabilize, potentially committing the planet to several additional feet of sea-level rise over centuries.

Even modest rises have outsized effects. A few inches of additional sea level can:

-

Turn rare floods into annual or monthly events

-

Dramatically amplify storm surge

-

Overwhelm drainage systems, levees, and seawalls

-

Accelerate coastal erosion and saltwater intrusion

A Timeline of Risk, Not a Sudden Collapse

Scientists frame the threat from Thwaites as a progression:

-

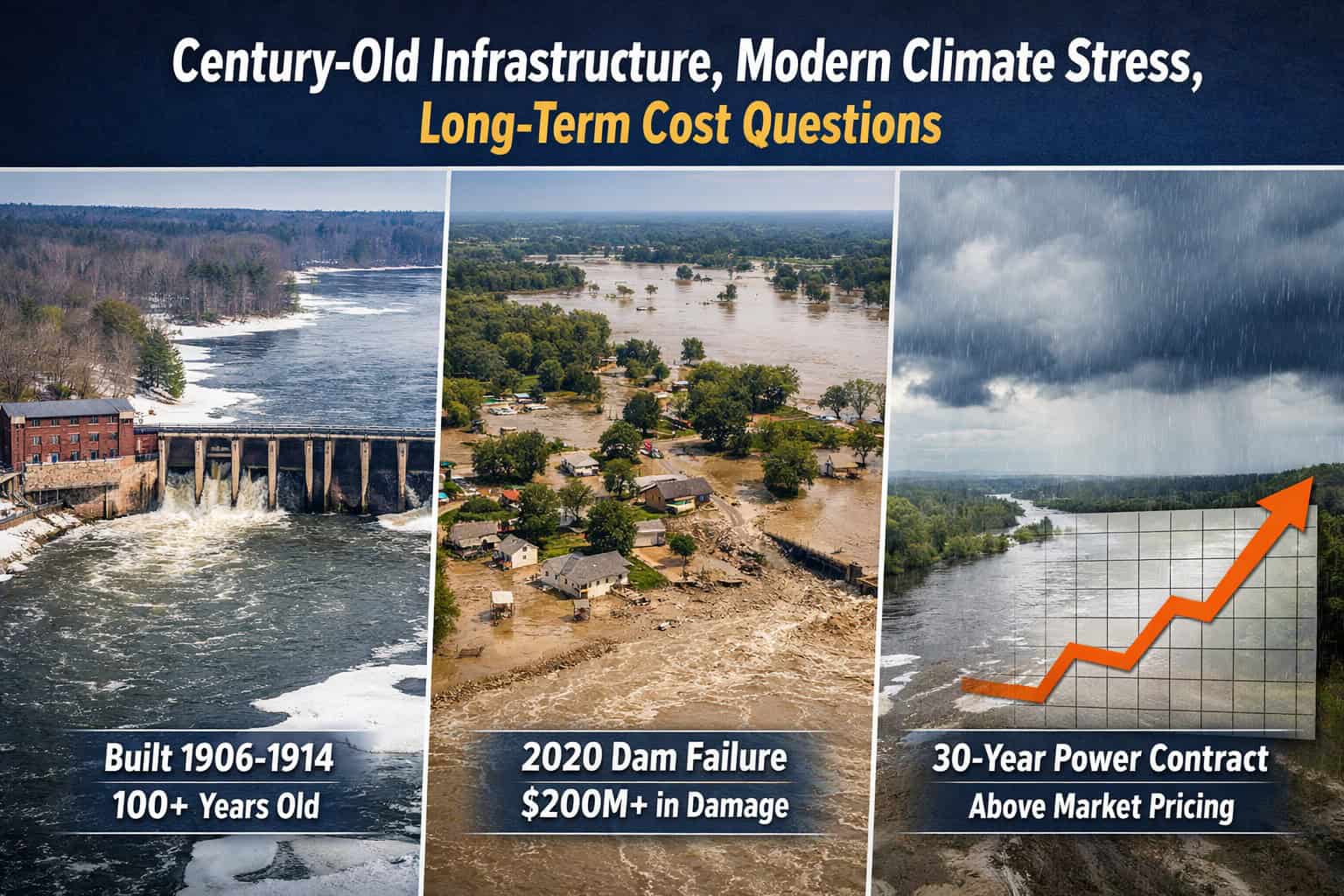

Now through the 2030s: Continued cracking and thinning accelerate ice flow. Sea-level rise remains incremental, but flooding worsens due to higher tides and stronger storms.

-

2035–2070: Likely loss of large sections of the ice shelf and accelerated retreat of the grounding line, locking in future sea-level rise even if warming slows.

-

Late 21st century and beyond: Thwaites may cross thresholds where recovery is no longer possible, raising the risk of broader West Antarctic ice loss. The most dramatic sea-level rise would unfold over centuries, but the commitment would already be made.

Coastal Cities on the Front Lines

Sea-level rise affects coastlines unequally. Some cities are already feeling the pressure:

-

Today: Miami, New Orleans, and Jakarta experience frequent tidal flooding and storm surge impacts because of low elevation and subsidence.

-

Mid-century stress zones: New York City, Boston, Houston, and Shanghai are projected to see more intense storm surge and infrastructure strain as baseline sea levels rise.

-

Long-term exposure: Even cities with flood defenses—like San Francisco and London—will need costly, ongoing engineering upgrades to remain resilient.

The Human Toll: Displacement on a Massive Scale

The human implications are vast. Estimates suggest that roughly 300 million people worldwide now live in coastal areas that could experience chronic flooding by 2100 under about one meter of sea-level rise—an outcome made more likely by continued Antarctic melting. Many more live just beyond the highest-risk zones, facing escalating costs, property loss, and climate-driven relocation pressure. These displaced populations would add up to one of the largest human migrations in modern history.

A Story of Urgency, Not Immediacy

The new fracture analysis underscore how Thwaites is already changing—not with a single dramatic collapse, but with a clear trend toward faster structural failure that mirrors broader climate shifts.

Scientists caution that the glacier’s name shouldn’t suggest a countdown to a sudden apocalypse. Instead, it signals that Earth’s climate system is entering a new phase, where slow, compounding changes have fast-moving consequences for humanity.

Thwaites Glacier is a warning—one that shows both how sensitive the climate system has become and how deeply interconnected distant ice and urban life truly are. What happens at Antarctica’s edge today will shape coastlines, cities, and communities around the globe for generations.

A Narrowing Window to Act—and a Chance to Change the Outcome

That means accelerating the transition to clean energy, electrifying transportation and buildings, tightening methane controls, and protecting forests and wetlands that naturally absorb carbon. At the same time, governments and cities can buy precious decades by investing in climate-resilient infrastructure, restoring coastal ecosystems like mangroves and wetlands, and planning smart adaptation rather than reacting to disaster.

None of these steps is simple, and none offers a single silver bullet—but taken together, they can slow the pace of warming, reduce the scale of ice loss, and keep the worst outcomes from becoming inevitable. The fate of the ice caps is not sealed yet, but the window to act is narrowing—and what’s done in the next few years will echo along coastlines for generations.