Imagine the vastness of the world’s oceans. Now, picture an underwater realm three times that size, not spread across the planet’s surface but hidden deep beneath it. A team of scientists has recently uncovered a monumental discovery — a colossal ocean trapped 700 kilometers beneath the Earth’s surface. This find is rewriting what we know about the Earth’s water and its origins.

Unveiling Earth’s Hidden Hydrosphere

The discovery of this hidden ocean has given researchers fresh insight into the origins of Earth’s water. This subterranean water, found in a mineral called ringwoodite within the Earth’s mantle, is so vast that it triples the volume of all the surface oceans combined. This unprecedented discovery challenges the long-standing theories about the origins of Earth’s water and suggests that water may not have arrived from comet impacts as some theories propose. Instead, it could have seeped from the Earth’s very core.

The Science Behind the Discovery

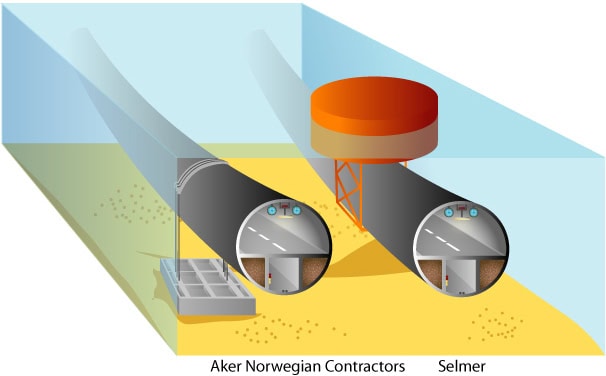

The team of researchers, led by Steven Jacobsen from Northwestern University, made this discovery using seismic waves. These waves, which travel through the Earth’s layers, slow down when passing through water-rich rocks, revealing the existence of this hidden ocean. Jacobsen explained that this find serves as tangible evidence that much of the Earth’s water came from within the planet, possibly explaining why the size of Earth’s oceans has remained consistent over millions of years.

This subterranean water could also reshape our understanding of the Earth’s water cycle. The water is stored between the grains of rock, suggesting that the Earth’s mantle might play a crucial role in regulating the planet’s water over long periods. Jacobsen emphasized that without this hidden water, much of the planet might be submerged, with only the tallest mountain peaks emerging above the surface.

This discovery is only the beginning. Scientists are eager to gather more data from seismic networks around the world to understand how common this mantle water phenomenon is. Their findings could potentially change how we think about Earth’s hydrological processes and the fundamental workings of our planet.

Read more at WECB