NORWAY – A speculative proposal making the rounds again in global infrastructure circles imagines a 3,400-mile tunnel beneath the Atlantic Ocean, capable of moving passengers between New York and London in under an hour.

Highlighted recently by Ecoportal, the concept carries a staggering $20 trillion price tag and relies on a combination of vacuum-tube travel and magnetic levitation to achieve speeds well beyond conventional rail or aircraft.

No government, engineering consortium, or private investor has committed to the idea, and no formal design exists. Yet the renewed attention matters for a different reason: many of the underlying technologies required already exist, at least in early or adjacent forms. The debate has shifted from science fiction to whether existing systems can be scaled, integrated, and operated at unprecedented distances.

Vacuum Tubes: Removing the Biggest Speed Barrier

At ultra-high speeds, air resistance becomes the primary enemy of efficiency. The proposed Atlantic tunnel would likely operate in a near-vacuum environment, reducing air pressure inside the tube to a fraction of normal atmospheric levels.

Lower pressure dramatically cuts drag, allowing vehicles to travel far faster while using less energy than aircraft. This same principle underpins Hyperloop-style transport, which has been tested on short tracks around the world. While no commercial vacuum-tube system exists today, experiments have validated the physics, showing that once air resistance is minimized, speed and efficiency scale rapidly.

For long-distance travel, vacuum tubes are not optional — they are foundational.

Magnetic Levitation: Eliminating Mechanical Friction

Inside the tube, vehicles would almost certainly rely on magnetic levitation (maglev) rather than wheels.

Maglev technology is already proven:

-

Commercial systems operate in Japan, China, and South Korea

-

Test trains have exceeded 370 mph

-

Maglev eliminates rolling friction, reducing wear and maintenance

In a low-pressure tube, maglev becomes even more powerful. Engineers estimate that speeds exceeding 3,000 mph are theoretically possible, constrained less by propulsion and more by passenger comfort, structural tolerances, and safety systems.

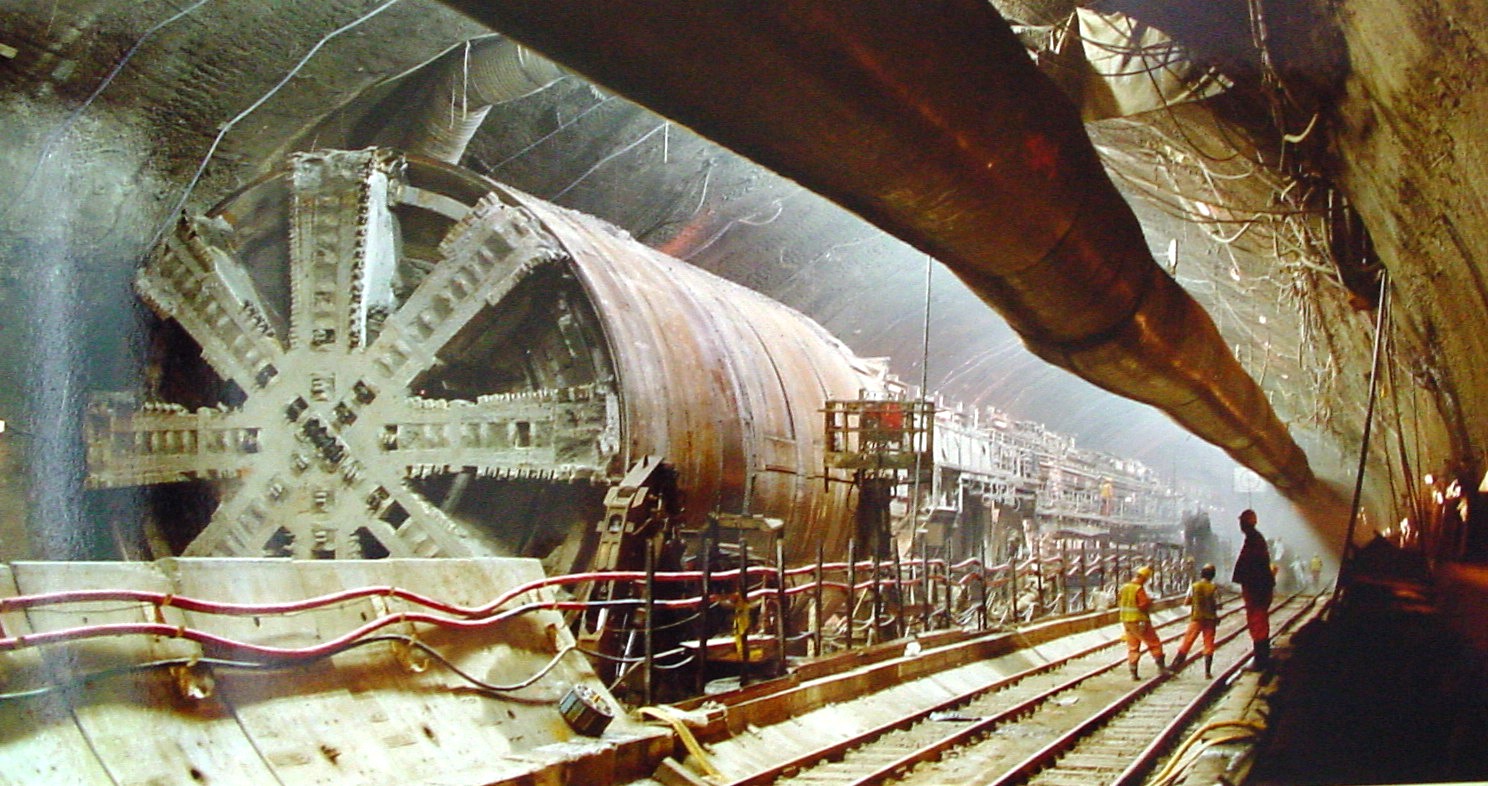

Lessons From the Channel Tunnel — and Their Limits

Undersea tunneling itself is not new. The Channel Tunnel, linking the UK and France beneath the English Channel, has operated since 1994. Stretching roughly 31 miles underwater, it relies on advanced tunnel-boring machines (TBMs), continuous concrete linings, and extensive safety systems.

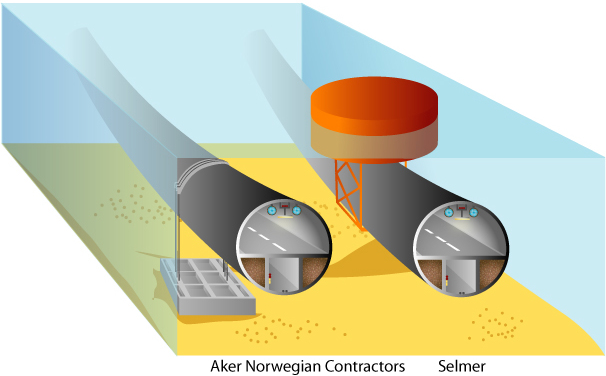

But scale is the defining challenge. A trans-Atlantic tunnel would be more than 100 times longer than the Channel Tunnel, pushing today’s TBMs beyond their practical limits. Engineers studying long-distance tunnels suggest future designs would require:

-

Multiple parallel tubes for redundancy and maintenance

-

Segmented pressure zones to isolate failures

-

Continuous AI-driven structural monitoring

Some researchers are also exploring submerged floating tunnels, which would be suspended underwater and anchored rather than bored through bedrock. While promising for deep crossings, no such system has yet been built at scale.

Materials and Monitoring: Building a “Living” Structure

A tunnel operating thousands of feet below sea level would face constant pressure, seismic forces, corrosion, and thermal stress. Traditional steel and concrete alone may not be sufficient.

Candidate technologies include:

-

Self-healing concrete that seals microcracks

-

Carbon-fiber-reinforced composites

-

Embedded fiber-optic and sensor networks

Rather than static infrastructure, such a tunnel would function as a continuously monitored digital system, detecting strain, leaks, and structural fatigue in real time — more akin to aerospace engineering than conventional rail.

Power, Control, and Safety Systems

At intercontinental distances, operational complexity rivals construction difficulty. A functional system would need:

-

Distributed power generation and storage

-

Autonomous traffic and speed control

-

Compartmentalized pressure and ventilation systems

-

AI-driven emergency response

In practice, the tunnel would operate like a hybrid of rail network, spacecraft, and data center, with redundancy built into every layer.

Where Michigan Fits Into the Technology Stack

While a trans-Atlantic tunnel remains speculative, Michigan is already deeply involved in many of the enabling technologies.

University of Michigan

The University of Michigan leads research in:

-

Advanced materials and composites

-

Autonomous systems and AI control

-

Structural health monitoring using embedded sensors

Its work on AI-driven infrastructure monitoring and lightweight materials directly overlaps with the needs of ultra-long tunnels and next-generation transit systems.

Mobility, Electrification, and Control Systems

Michigan’s automotive and mobility supply chain is rapidly transitioning toward:

-

Electric propulsion

-

Power electronics and inverters

-

Precision motion control software

These same technologies are central to maglev systems, particularly at extreme speeds where efficiency and reliability are critical.

Advanced Manufacturing and Robotics

Michigan manufacturers remain global leaders in:

-

High-precision machining

-

Robotics and automation

-

Large-scale systems integration

Those capabilities would be essential for producing, assembling, and maintaining massive tunnel segments — whether bored underground or prefabricated for submerged systems.

Big Vision, Incremental Reality

The revived interest in a $20 trillion Atlantic tunnel is less about imminent construction and more about direction. Just as the Channel Tunnel required centuries of ideas before becoming reality, intercontinental fixed links will likely emerge gradually — first through regional megaprojects, then longer crossings.

For Michigan, the message is clear: the state is already building pieces of the future, even if the full vision remains far beyond the horizon.