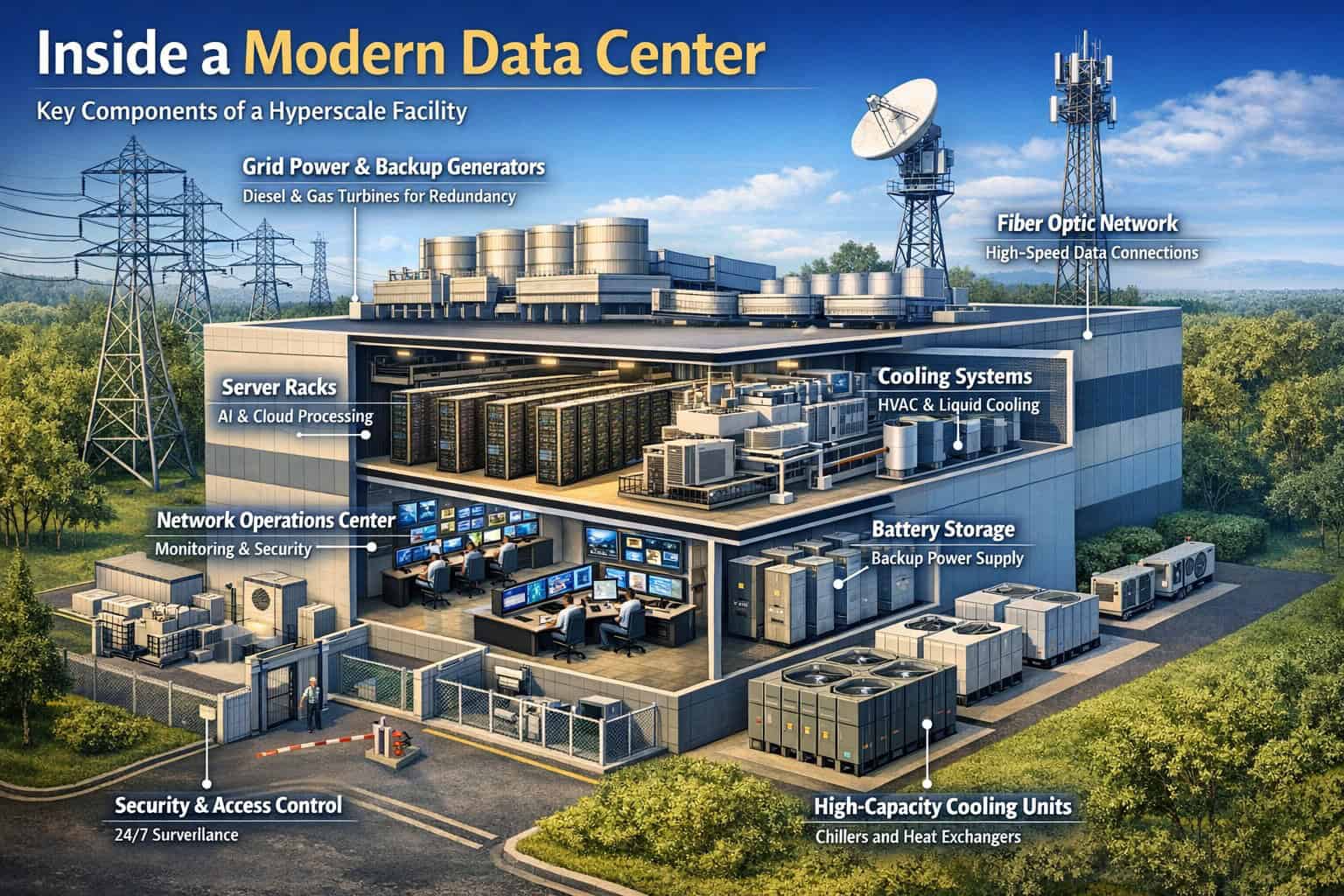

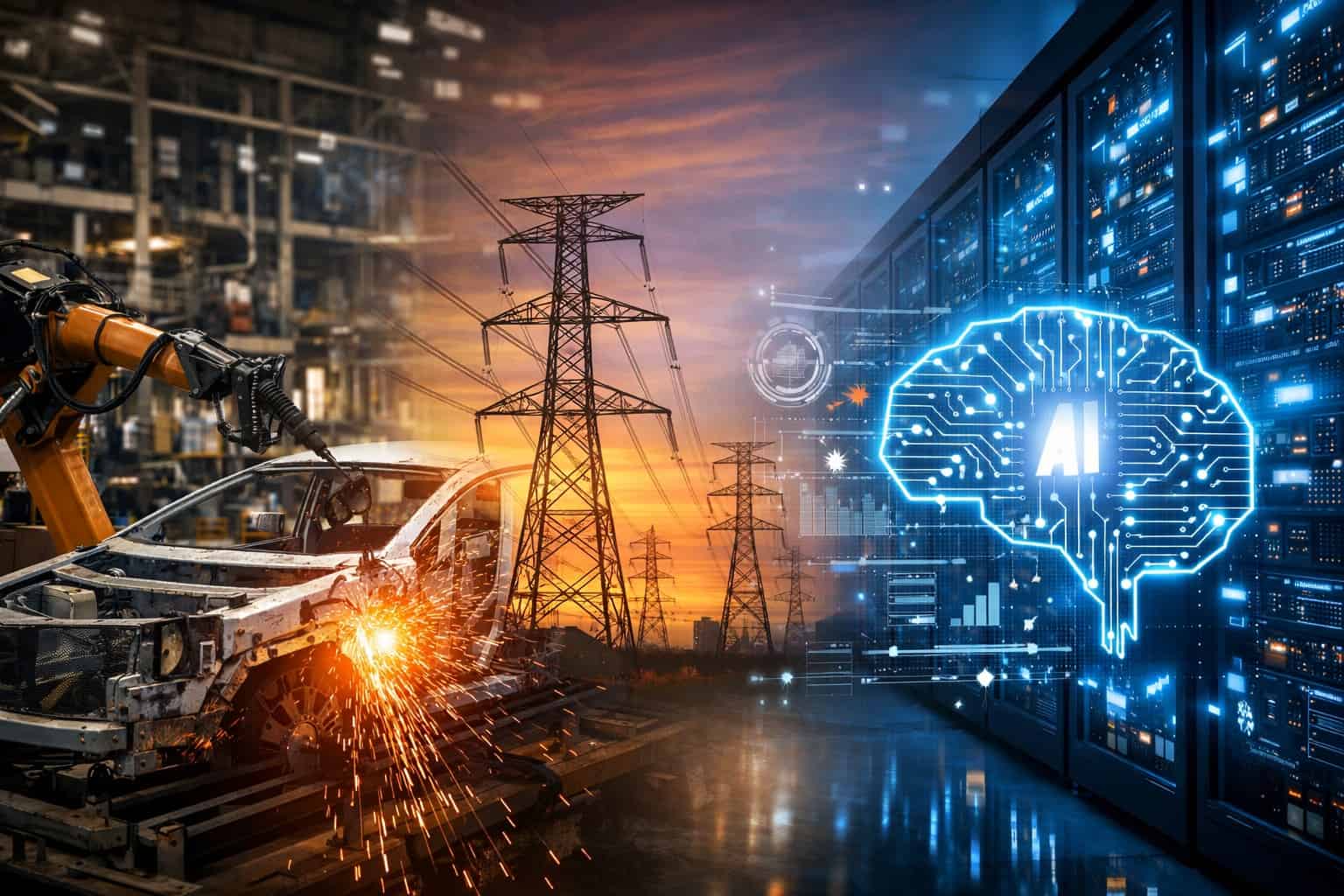

ANN ARBOR – A proposed $1.2 billion high-performance computing facility backed by the University of Michigan and Los Alamos National Laboratory has become the latest flashpoint in Michigan’s escalating backlash against data centers — a debate now centered as much on electric rates as on land use or environmental risk.

The project, planned for Ypsilanti Township, is being promoted as a national-scale research asset focused on artificial intelligence, scientific modeling and advanced computing. But local officials and residents say the facility raises the same concerns seen across Southeast Michigan: massive electricity demand, unclear long-term costs, and limited local control over decisions that could affect utility bills for decades.

Ypsilanti city leaders have passed a resolution urging a pause, citing unanswered questions about energy use, infrastructure upgrades and transparency. In Lansing, lawmakers are weighing whether to revoke a $100 million state grant tied to the project — a sign that skepticism toward large computing facilities has moved well beyond individual townships.

Michigan’s data center boom meets organized resistance

The U-M–Los Alamos project is not an outlier. Michigan has become a prime target for data center development, driven by its freshwater access, central location and utility infrastructure. Proposed facilities now stretch from Washtenaw County to Metro Detroit and westward — and almost every major proposal has triggered opposition.

In Saline Township, a controversial data center proposal tied to OpenAI and Oracle has drawn sustained protests over wetlands, zoning and water use. But the fight escalated when Dana Nessel formally opposed the project, warning that its enormous power demand could drive up electric rates for Michigan residents.

Her concern struck a nerve statewide.

Similar arguments have surfaced in Van Buren Township, where residents are pushing back against a proposed 1-gigawatt data center near I-94, and in multiple Washtenaw County townships where petitions and legal challenges have slowed or stalled rezonings.

What ties these battles together is a growing fear that ratepayers — not tech companies — will shoulder the long-term costs.

Why electric rates are already high in Michigan

Michigan residents are especially sensitive to that risk because electric rates here are already among the highest in the nation.

Several structural factors drive those costs:

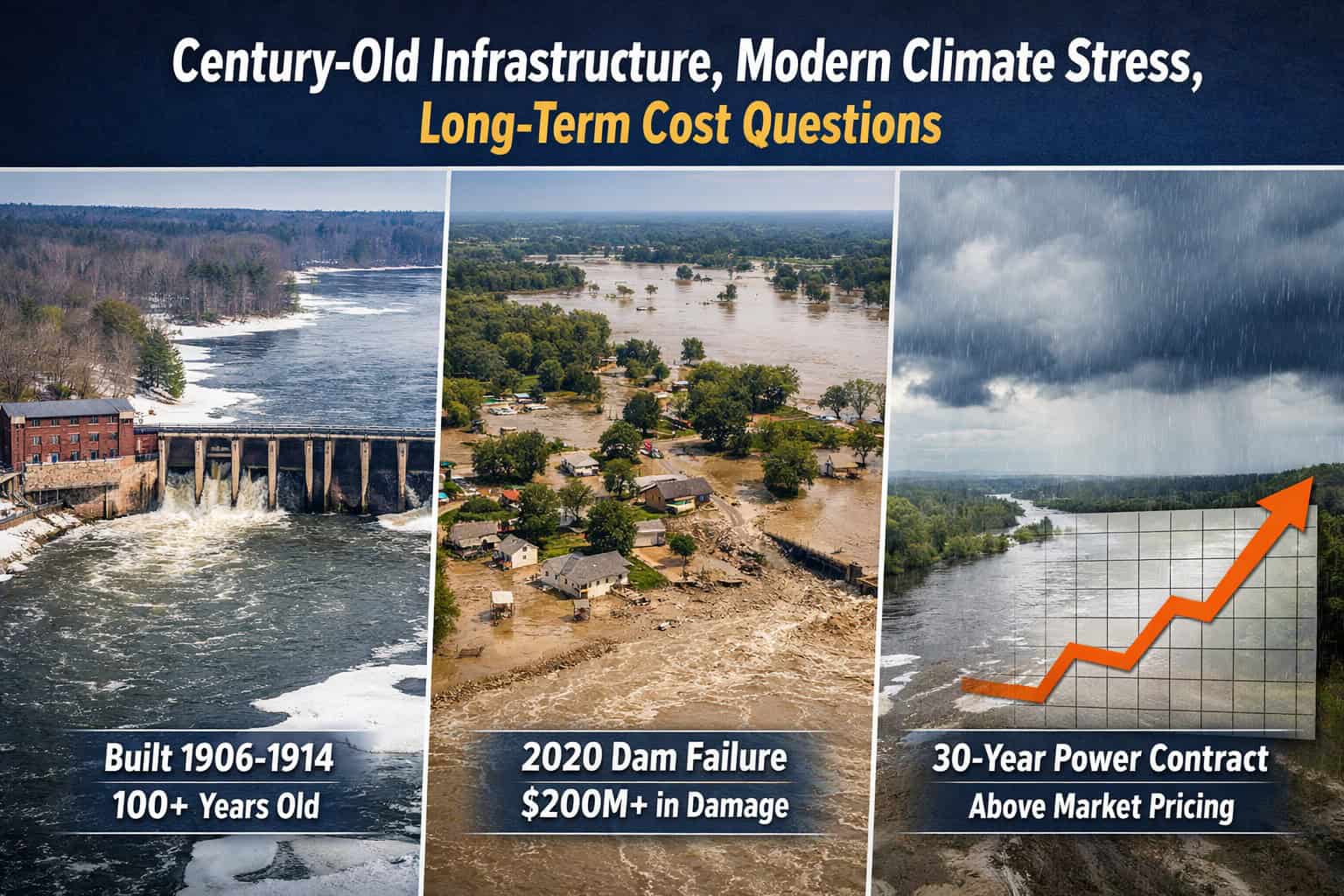

Aging infrastructure. Michigan’s electric grid is old, and utilities have spent billions replacing poles, wires and substations. Those capital costs are passed directly to customers through rate increases approved by regulators.

Utility monopoly structure. Most residents are served by regulated monopolies, primarily DTE Energy and Consumers Energy. With limited competition, utilities recover nearly all approved investments from ratepayers.

Reliability spending after outages. Following years of storm-related outages and public criticism, utilities have accelerated grid-hardening programs. While aimed at improving reliability, those investments have pushed bills higher.

Energy transition costs. Michigan’s shift away from coal toward natural gas and renewables requires new generation, storage and transmission — all capital-intensive projects embedded in electric rates.

Industrial load concentration. Large, energy-intensive users — including factories, crypto miners and now data centers — require major grid upgrades. Critics argue those upgrades often benefit a single customer but are socialized across the broader rate base.

Nessel’s warning in the Saline case zeroes in on that last point: when a data center consumes as much electricity as a small city, the grid must be reinforced — and someone has to pay.

Data centers and ratepayer risk

Utilities and developers argue that large data centers pay their fair share and bring investment, tax base and some high-wage jobs. But opponents counter that data centers employ relatively few people compared to their energy footprint — and that long-term grid costs can outlast initial economic benefits.

That concern now shadows the U-M–Los Alamos project as well.

University officials emphasize that the facility is research-focused, not a commercial cloud operation. But critics say electricity demand does not care whether servers are academic or corporate. Power drawn by supercomputers flows through the same grid and affects the same rate structures.

For residents already facing rising monthly bills, that distinction feels academic.

Local control versus statewide strategy

Michigan’s economic development strategy has leaned heavily into advanced technology, AI and research infrastructure. State leaders argue that falling behind in computing capacity would harm competitiveness.

But at the local level, communities are pushing back — not against technology itself, but against how decisions are made and who absorbs the risk.

In town after town, residents say projects arrive with limited disclosure, fast-tracked zoning and assurances that feel thin compared to the scale of what’s being built.

That tension — between statewide ambition and local consequence — is now defining Michigan’s data center debate.

A turning point

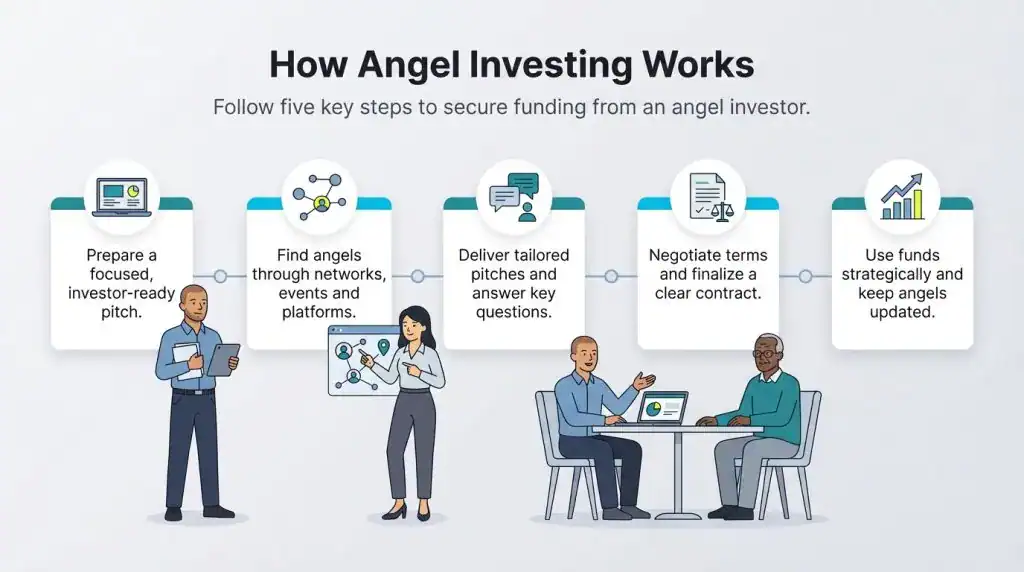

The backlash has reached Lansing. Lawmakers are considering bills to revisit data center tax incentives, tighten disclosure rules, and give regulators more authority to assess grid impacts before projects move forward.

What’s clear is that Michigan’s relationship with data centers has changed. These projects are no longer viewed simply as neutral engines of growth. They are being scrutinized as industrial-scale energy users in a state where electricity is already expensive and getting more so.

The U-M–Los Alamos supercomputer project now sits squarely in that reckoning — a high-profile research initiative caught in the same storm reshaping how Michigan weighs innovation against affordability, and progress against the power bill.