ANN ARBOR – Michigan is stepping into the fast-moving world of hyperscale data centers just as the industry’s biggest constraint becomes impossible to ignore: power.

Across the United States, the explosive growth of artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and digital services is driving a surge in demand for data centers—massive facilities that can consume as much electricity as a small city. Nationally, that demand is colliding with an aging power grid, slow permitting, and long utility interconnection queues. In Michigan, the same collision is now playing out in real time.

For state regulators and utilities, the question is no longer whether data centers are coming. It is how to serve them without shifting costs onto households and small businesses—or losing projects to states willing to bend the rules.

A national problem arrives in Michigan

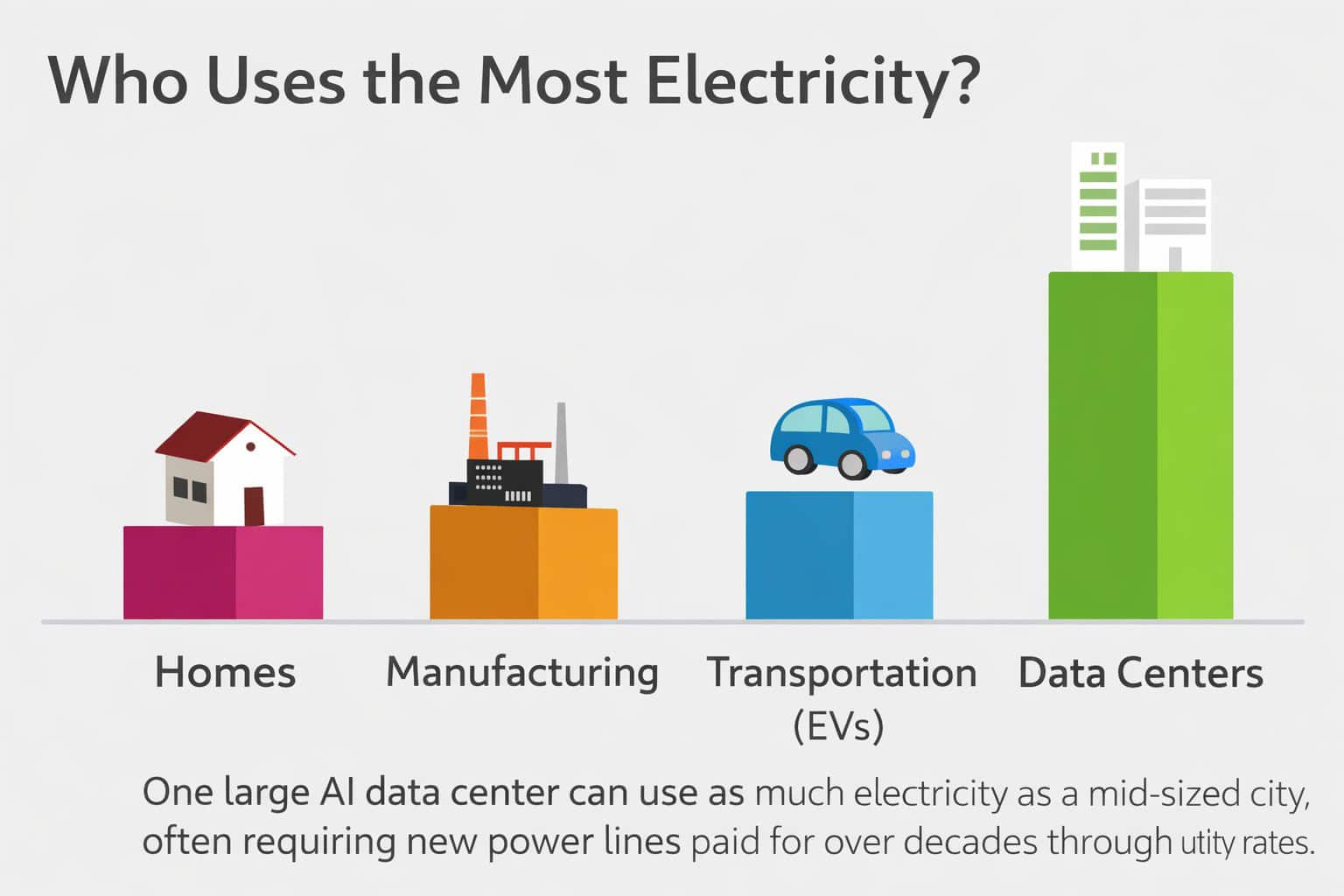

Data centers now account for roughly 4% of total U.S. electricity consumption, and multiple federal and industry forecasts suggest that share could double by the end of the decade as AI workloads accelerate. The challenge is not just the scale of demand, but its speed. A single hyperscale campus can require hundreds of megawatts of power, often arriving much faster than utilities are used to planning for.

National reporting by the Financial Times has documented how developers, faced with grid connection delays of five to seven years in some regions, are increasingly installing their own on-site power plants. Natural-gas turbines adapted from aircraft engines, large diesel generators, and hybrid battery systems are becoming common tools to bypass grid bottlenecks.

That trend matters in Michigan because it signals what happens when utilities cannot move fast enough: developers find workarounds, often at the expense of long-term energy and environmental goals.

The Saline test case

Michigan’s first high-profile hyperscale data center project near Saline Township has become a test case for how the state will handle this new wave of infrastructure. Regulators approved energy supply arrangements tied to the project late last year, but only with explicit conditions designed to protect ratepayers.

Those conditions reflect a growing concern among regulators and advocates: large, single-customer loads can trigger expensive grid upgrades, and if those costs are spread broadly, everyday customers end up subsidizing some of the most capital-rich companies in the world.

The Saline decision set an early tone. Michigan wants the economic development, construction activity, and tech credibility that hyperscale data centers can bring—but not at any price.

Two utilities, two paths

The debate looks different depending on where you stand on Michigan’s utility map.

In southeast Michigan, the pressure is landing squarely in the territory served by DTE Energy. That region combines proximity to Ann Arbor’s research ecosystem, Detroit’s industrial base, and major fiber routes—making it a natural target for data center developers.

For DTE, the issue is less about whether power can be delivered and more about how quickly and at what cost. Large industrial and data-center loads are arriving at the same time the utility is investing heavily in grid modernization and working toward state clean-energy requirements. Regulators are increasingly focused on ensuring that hyperscale customers pay for the infrastructure they require, rather than embedding those costs in general rates.

In Consumers Energy territory, the hyperscale spotlight has been quieter so far, but that may not last. Consumers serves much of western, central, and northern Michigan—regions with available land, growing manufacturing electrification, and fewer existing transmission corridors. As developers look beyond southeast Michigan, Consumers’ footprint could become the next frontier.

For regulators, the challenge is consistency. Decisions made in DTE territory will inevitably shape expectations for Consumers, even if the geography and grid conditions differ.

The “phantom load” risk

One of the biggest concerns nationally—and increasingly in Michigan—is what analysts call “phantom load.” Utilities must plan years in advance for large power users, but not every announced data center ultimately gets built, and not every project reaches full scale.

If utilities overestimate future demand, they risk overbuilding generation and transmission infrastructure. If that happens, the costs do not disappear; they land on ratepayers. Michigan regulators have signaled they want firm commitments, not speculative projections, before approving long-term investments tied to data center growth.

That caution may slow some projects, but it also reflects lessons learned elsewhere, where aggressive build-outs have left utilities and customers exposed when demand forecasts failed to materialize.

Bring-your-own power: a warning sign

The national shift toward on-site generation should be a warning sign for Michigan policymakers. When grid timelines stretch too long, developers do not wait—they build around the system. While that keeps projects moving, it can also mean more fossil-fuel generation operating outside traditional utility oversight.

For a state that has set ambitious clean-energy goals, widespread “bring-your-own-power” data centers could complicate emissions targets and air-quality management. It could also weaken the role of utilities just as grid coordination becomes more important.

A narrow path forward

Michigan is trying to thread a narrow needle: remain competitive for AI-era infrastructure while protecting customers and maintaining control over its energy transition. That means clearer rules on who pays for upgrades, stronger forecasting standards, and faster—but disciplined—grid planning.

The stakes are high. Done right, hyperscale data centers can anchor Michigan in the next generation of the digital economy. Done poorly, they could fuel higher electric bills, public backlash, and a loss of trust in the state’s energy governance.

The data center boom is no longer a distant coastal story. It is here, and in Michigan, it is forcing hard choices about power, policy, and who ultimately bears the cost of the AI revolution.