ANN ARBOR – A dramatic new test-flight video released by a California aviation startup has reignited one of technology’s oldest promises: the flying car. The footage shows a compact electric vehicle lifting vertically from the ground, hovering smoothly, and settling back down under full control—a small flight by aviation standards, but a major psychological milestone for an industry long stuck between science fiction and engineering reality.

The video arrives at a moment when flying cars and closely related electric vertical takeoff and landing aircraft—known as eVTOLs—are moving out of concept art and into early test programs. Advances in battery energy density, electric propulsion, lightweight materials, and AI-assisted flight controls have quietly reshaped what is technically possible.

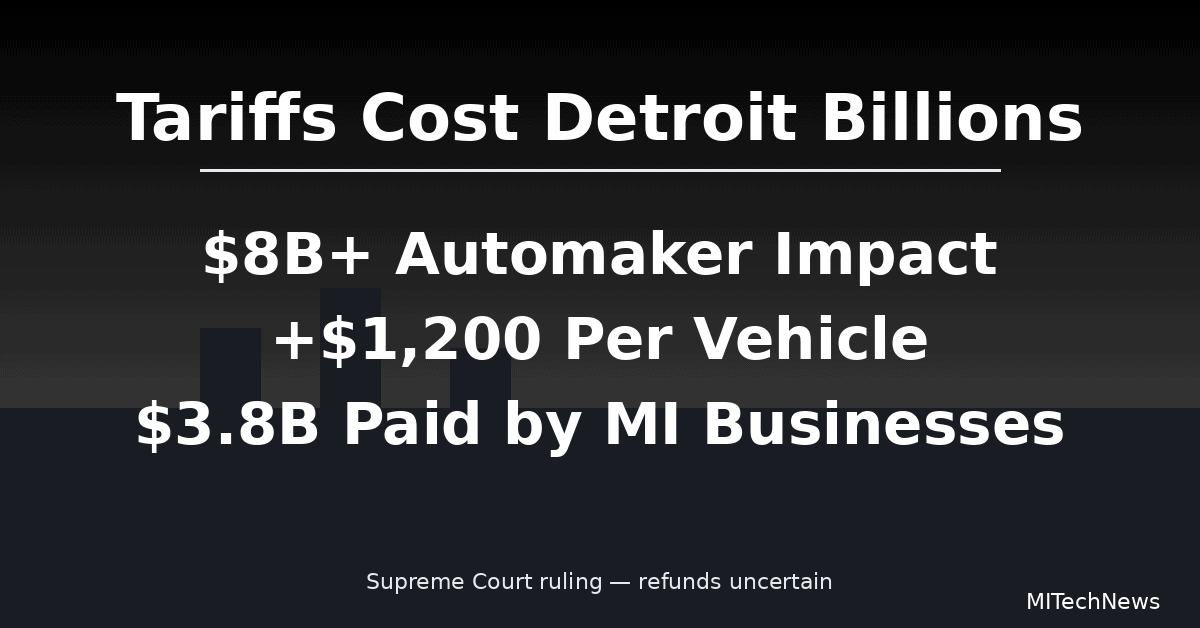

But the bigger question, especially in Michigan, is no longer whether flying cars can work. It’s whether Detroit will be part of what comes next.

A Growing Field Beyond the Viral Clip

One of the most visible entrants is Alef Aeronautics, whose Model A is designed to be both street-legal and capable of vertical flight. Alef’s approach avoids runways entirely, positioning the vehicle as a hybrid between an EV and a personal aircraft. The company has said it is targeting early customer deliveries following expanded testing and regulatory review.

“Alef is interesting because it’s trying to meet consumers where they already are—on roads,” said Richard Aboulafia, managing director at aerospace consultancy AeroDynamic Advisory. “That’s ambitious, but it also means solving two regulatory problems instead of one.”

Other companies are taking different routes.

Samson Sky is betting on transformation rather than vertical lift. Its Switchblade converts from a road vehicle into a runway fixed-wing aircraft in minutes, trading VTOL complexity for longer range and higher cruise speeds—at the cost of needing a runway.

Meanwhile, ASKA is targeting a broader footprint. Its four-seat ASKA A5 uses a hybrid propulsion system and fold-out wings, aiming for family and commercial use cases rather than individual pilots.

“These aren’t all flying cars in the Jetsons sense,” said Seth Goldstein, equity strategist at Morningstar. “Some are closer to airplanes that can drive. Others are cars that can fly briefly. The market hasn’t decided which definition will win.”

eVTOLs: The Adjacent Market Moving Faster

While roadable flying cars grab headlines, many analysts believe eVTOL aircraft—vehicles that never touch public roads—may reach scale sooner.

Startups like Doroni Aerospace are focusing on short-range personal flight, with simplified controls and fully electric propulsion. These vehicles bypass automotive regulations altogether, focusing instead on FAA certification and controlled airspace operations.

“Urban air mobility is where the near-term revenue is,” said Aboulafia. “Flying cars are compelling, but air taxis and personal eVTOLs may get approved first because the use cases are narrower.”

Are Flying Cars a Threat to Michigan’s Auto Industry?

At first glance, flying cars might appear to threaten Michigan’s auto dominance. Many of the most advanced prototypes are emerging from California, Europe, and Asia—not Detroit. And aviation startups operate under a very different regulatory and cultural framework than traditional automakers.

But most analysts see overlap, not displacement.

“The technology stack is almost identical to EVs,” said Goldstein. “Electric motors, battery packs, power electronics, sensors, software. If you strip away the wings, you’re still looking at something Detroit understands extremely well.”

Automakers like General Motors and Ford Motor Company have already invested billions in electric drivetrains, autonomous systems, and advanced manufacturing—technologies that flying-car developers rely on heavily.

Where Michigan could lose ground is if flying-car startups vertically integrate, keeping high-value engineering and production in-house and bypassing traditional suppliers. But if flying cars scale beyond boutique volumes, analysts say Detroit’s manufacturing expertise becomes hard to ignore.

“At some point, aerospace startups run into the same problem Tesla did early on—how do you build this reliably, at scale?” said Aboulafia. “That’s where Michigan historically excels.”

Detroit’s Next Mobility Test

Flying cars may represent Detroit’s next mobility stress test, similar to earlier transitions involving hybrids, EVs, autonomy, and connected vehicles.

Each shift followed a familiar pattern: skepticism, early outsiders gaining attention, then legacy players adapting—or falling behind.

“This is not an existential threat today,” said Goldstein. “But it’s a signal. Mobility is being redefined again, and the question is whether Detroit participates early or reacts late.”

For Michigan suppliers, the opportunity may come quietly. Battery enclosures, thermal management systems, lightweight composites, embedded software, and advanced sensors are already part of the state’s industrial base. Flying-car and eVTOL programs could become adjacent revenue streams, even if final assembly happens elsewhere.

The risk, analysts say, isn’t that flying cars replace automobiles. It’s that new mobility categories mature without Michigan fully plugged into the value chain.

A Slow Takeoff, Not a Sudden Leap

Despite the excitement, flying cars are unlikely to flood suburban garages anytime soon. Early vehicles will be expensive, tightly regulated, and limited to niche use cases. Infrastructure, airspace management, and public acceptance remain major hurdles.

But each successful test flight—each viral video—pushes the industry one step further from fantasy and closer to function.

What matters now is not whether flying cars arrive overnight, but who helps build them when they do.

For Detroit, the next mobility era may not come on four wheels alone—but it doesn’t have to pass Michigan by either.