SAN FRANCISCO – “I think we are at an important moment for science and artificial intelligence (AI). In the last two or three years, we’ve seen AI tools become powerful enough and mature enough to tackle really important real-world problems.” That’s according to Demis Hassabis, one of the most influential yet elusive figures in the field. The 48-year-old British thinker is the founder and CEO of Google DeepMind, the AI research division of the tech giant, and the recent winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Though small and reserved in appearance, Hassabis commands attention wherever he goes. He’s often accompanied by a small entourage, like a rock star, and dresses in Silicon Valley style: a blue shirt, black blazer, jeans, and sneakers. His public appearances are rare, as are the interviews he gives. In London, he agrees to speak briefly with around 20 international journalists, including EL PAÍS, during the AI for Science forum organized by his company and The Royal Society. There, he delivers his thoughts with rapid-fire precision while steering clear of more political questions, such as what he expects will happen with AI regulation when Donald Trump returns to the White House in January. This self-restraint is helped by the fact that he has James Manyika, Google’s vice president of research, at his side.

At Monday’s meeting with journalist, Hassabis shared a thought that directly challenges the claims of some of his competitors: “Large multimodal models of generative AI [those capable of interpreting text, images, and videos] are going to be a critical part of the overall solution to developing artificial general intelligence [AGI, which matches or surpasses human intelligence], but I don’t think they’re enough on their own. I think we’re going to need a handful of other big breakthroughs before we get to what we call AGI,” says the former chess prodigy. This statement stands in contrast to the predictions of figures like Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, and Elon Musk, technology entrepreneur with a posting in the new Trump administration, both of whom claim that superintelligence is just around the corner.

As one of the foremost figures in the AI world, Hassabis’ perspective carries significant weight. In 2023, Google entrusted him with leading AI research, merging his company, DeepMind — which previously functioned as an independent research lab — into Google’s broader AI initiatives. This integration has led to a swift push for tools like Gemini and other generative AI technologies.

However, Hassabis’ true breakthrough came just a month ago, when he and two colleagues from DeepMind won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their development of AlphaFold, an AI tool capable of predicting the structure of the 200 million known proteins. This achievement would have been nearly impossible without AI, and solidifies Hassabis’ belief that AI is set to become one of the main drivers of scientific progress in the coming years.

Hassabis — the son of a Greek-Cypriot father and a Singaporean mother — reflects on the early days of DeepMind, which he founded in 2010, when “nobody was working on AI.” Over time, machine learning techniques such as deep learning and reinforcement learning began to take shape, providing AI with a significant boost. In 2017, Google scientists introduced a new algorithmic architecture that enabled the development of AGI. “It took several years to figure out how to utilize that type of algorithm and then integrate it in hybrid systems like AlphaFold, which includes other components,” he explains.

“During our first years, we were working in a theoretical space. We focused on games and video games, which were never an end in themselves. It gave us a controlled environment in which to operate and ask questions. But my passion has always been to use AI to accelerate scientific understanding. We managed to scale up to solving a real-world problem, such as protein folding,” recalls the engineer and neuroscientist.

When asked if there are any areas of science where AI can’t make an impact, Hassabis responds: “I think we are well suited to help solve those problems that can be described as a big search through a combinatorial space. You need to be able to build a model and describe the goal in terms of a metric. For example, in protein folding, minimize the error between the actual and predicted positions of the atoms.”

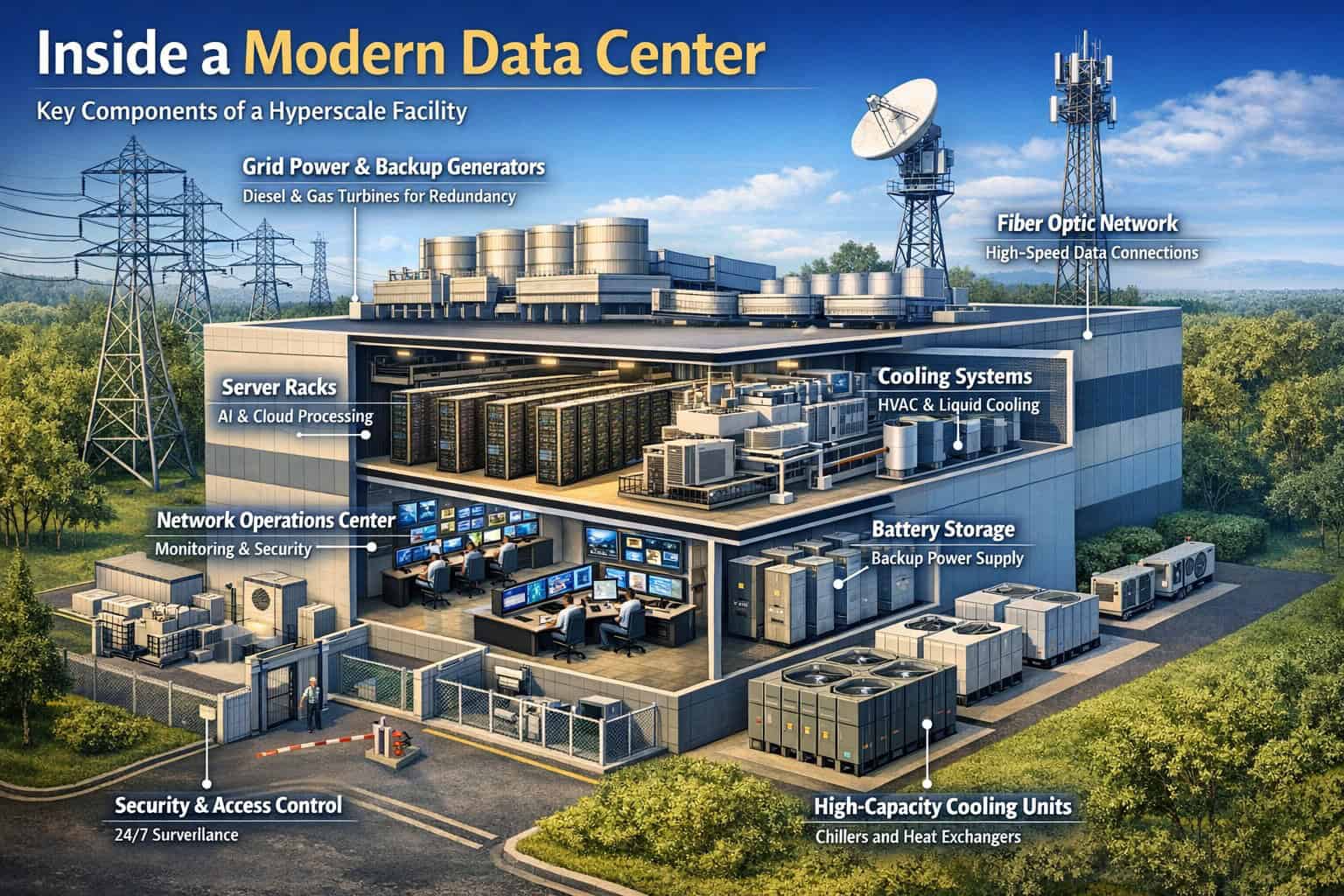

The conversation also touched on the environmental concerns associated with AI, particularly its energy and water consumption. When asked if he is worried about its environmental footprint, Hassabis replies: “My view is that the benefits of these systems will far outweigh their energy usage. Tools for weather forecasting, power grid optimization or materials design will help solve climate change. I mean, we’ve got to try geopolitically as well, but that seem to be not working very well. So I would try technical solutions: new battery designs, new superconductors, nuclear fusion. That’s what AI can bring to the table.”