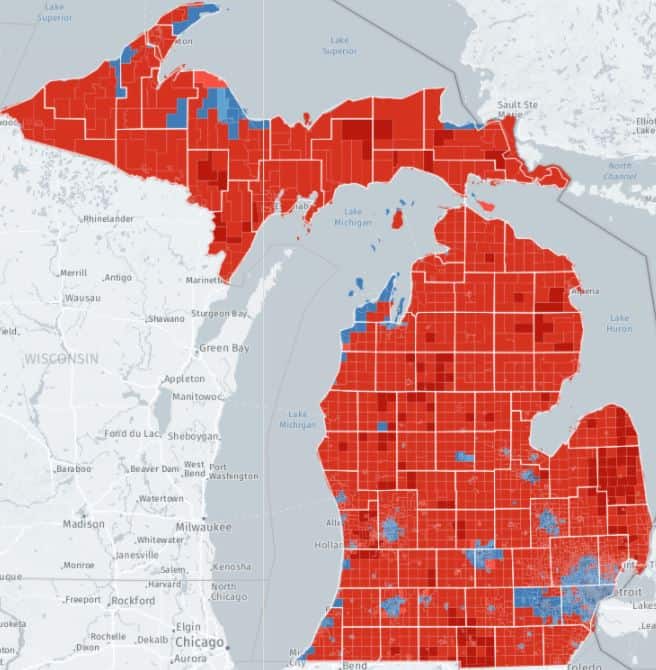

LANSING – Based on known markers for the pollutants, Michigan waters are being affected by septic tank effluents in the winter and cattle manure in the spring and summer, presenters at a symposium by the Michigan Agri-Business Association said.

Controlling the former would mean additional controls on septic tanks, while controlling the latter could be done through more education and some financial assistance for farmers, presenters said.

Joan Rose, a microbiologist at Michigan State University, said some recent studies showed substantial portions of the state’s watersheds showed some evidence of human waste, based on markers in that waste, during the winter when water flow was lower.

As snow melted or summer rains came, she said those studies showed similar infusions of cattle manure into those streams. The tests, she said, could not differentiate between manure that came from cattle farms directly and what had been applied to crop fields.

Rose said the septic tank pollution was a particular concern. “We were surprised to see septic tanks show up with the human marker,” she said.

But she noted a study in Macomb County that showed some half of the septic tanks were faulty at any given time.

Some of the cattle contamination can be reduced by better controlling field drains, Charlie Schafer, CEO of Ecosystems Services Exchange, and Larry Brown, an extension agricultural engineer at Ohio State University, said in their presentations.

Schafer said reducing water flow from fields can create an equivalent reduction in contribution of phosphorus and nitrogen to neighboring waters.

“That’s the only way you’re going to control water quality,” Mr. Brown said of controlling water flow from fields.

He noted that the buffer strips that have become popular in recent years do little if the field drains run under them.

He said his school has been experimenting with a number of systems for both controlling water flow and filtering out nutrients and other contaminants before the water is released.

Schafer said controlling the flow can also benefit farmers.

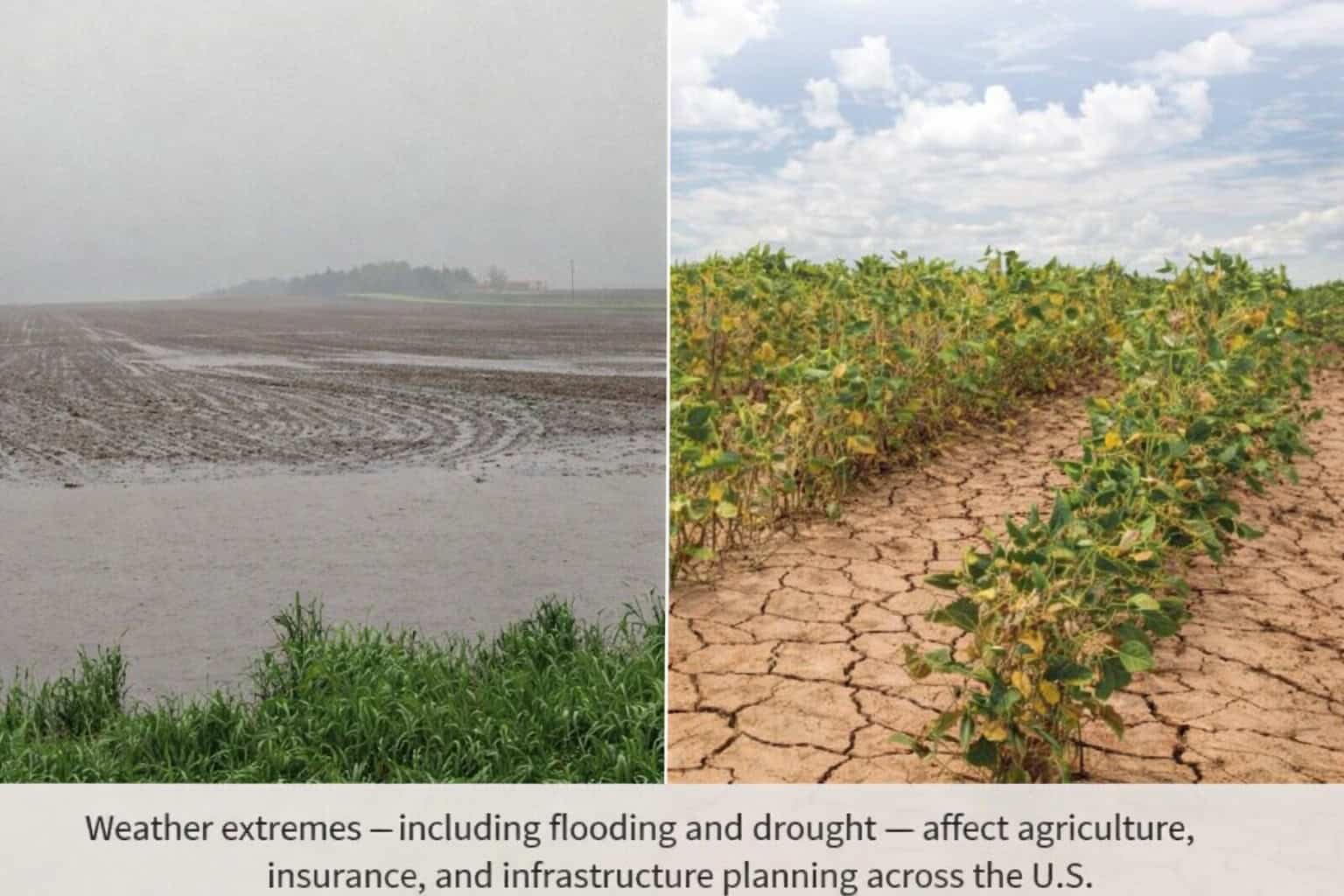

“Two-thirds of corn loss and half of soy bean loss is the result of too wet, too dry, many times the same year,” he said.

Holding some of the water under the fields reduce at least the too dry concerns, both said.

The concern: convincing farmers to make the changes.

“So many of these practices don’t create an on-farm benefit,” Mr. Schafer said. “They’re slow to adopt. Economics always plays a role.”

He said there are programs to help farmers cover some of the costs, but there is still need to inform farmers both about the systems and about that funding.

Rose said for particularly egregious pollution sources, there is an expanding number of diagnostic tests that can help to locate the source, and she urged the state to use those more often.

The state also needs to design more of its regulations around watersheds rather than municipal boundaries, she said. “There needs to be a consolidation and coordination of efforts,” she said.

The story was published by Gongwer News Service. To subscribe, click on www.gongwer.com